Chronic Lower Back Pain Chiropractor

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is defined as persistent pain in the lumbar region lasting three months (12 weeks) or longer. Unlike acute low back pain, which typically resolves relatively quickly, CLBP often involves complex biological and psychological changes that require a specialised, long-term management strategy focused on restoring function.

In Australia, the burden of CLBP is immense. Back problems affect approximately 4.0 million Australians, or 16% of the population. This high prevalence underscores that many Australians struggle daily with compromised quality of life, mobility restrictions, and limitations in their ability to work and participate in social activities.

Many individuals struggling with CLBP seek conservative, non-pharmacological care options to manage their persistent pain. Chiropractic care is frequently chosen for its focus on assessment, manual therapy, and movement rehabilitation. At Ringwood Chiropractic, the goal of treatment is not merely to provide temporary pain relief, but to assess the underlying biomechanical and lifestyle factors contributing to the persistence of the pain, ultimately helping patients restore movement and maintain an active life. The approach prioritises patient education, active self-management, and evidence-based interventions tailored to the individual’s specific circumstances.

What is Chronic Low Back Pain?

CLBP affects the structures of the lower spinal column, which includes the five lumbar vertebrae, the intervertebral discs that cushion them, the small paired facet joints, the supporting ligaments, and the large, stabilising paraspinal muscles. When pain persists beyond the typical healing time, clinicians classify it as chronic.

For decades, many cases of persistent back discomfort were broadly labelled “nonspecific low back pain” because a single source of pain could not be definitively identified. However, clinical understanding has evolved significantly. Today, much of this type of persistent pain is better understood as degenerative chronic low back pain (degenerative cLBP). This term describes pain linked to degenerative alterations that occur in the discs, facet joints, and supporting ligaments of the spine, often accompanied by regional or global changes in spinal alignment.

The Complexity of Chronic Pain Mechanisms

Chronic pain often involves mechanisms far more complex than simple tissue injury. Pain can be categorised based on its mechanism:

-

- Nociceptive Pain: Pain resulting from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue (e.g., a strained muscle or an irritated joint).

-

- Neuropathic Pain: Pain arising from nerve involvement (e.g., sciatica).

-

- Nociplastic Pain: Pain that arises from altered nociception (nervous system processing) despite no clear evidence of ongoing tissue damage or nerve lesion. This suggests the nervous system itself has become sensitised, amplifying pain signals—a phenomenon often referred to as central sensitisation.

Because chronic pain involves these complex interplay of factors, effective management requires addressing structural issues (degenerative cLBP) alongside the influence of the altered nervous system and lifestyle factors.

The profound impact of CLBP in Australia is evidenced by data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW):

Australian Health Burden of Back Problems

| Measure | Statistic (2022/2023 Australian Data) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 4.0 million (16%) Australians affected | 1 in 6 people in the community require management. |

| Disease Burden Rank | Third leading cause of total disease burden | Highlights the severe impact on functional years of life. |

| Comorbidity Rate | 72% live with 1+ other chronic condition (43% mental/behavioral) | Demonstrates the holistic, physical, and psychological nature of the problem. |

How Does the Condition Happen?

CLBP is rarely caused by a single, catastrophic event. It is typically multifactorial, stemming from an accumulation of biomechanical demands, postural issues, and psychosocial stressors.

Biomechanical and Physical Contributors

Persistent mechanical loads are primary physical contributors to CLBP. These include repetitive movements, improper lifting techniques, and prolonged static work postures. When the spine is consistently held in positions that strain supporting structures—such as sitting slumped for extended periods—it places undue stress on the intervertebral discs and facet joints, contributing to degenerative alterations.

Furthermore, lifestyle factors play a major role. Inadequate physical activity and poor overall spinal conditioning (e.g., weak core muscles) reduce the spine’s ability to absorb shock and maintain stability, increasing vulnerability to mechanical strain.

The Critical Role of Psychosocial Factors (Yellow Flags)

A crucial distinction in chronic pain management is understanding the non-physical factors that prolong disability. These are often termed “Yellow Flags” and represent psychosocial risk factors for long-term functional decline and work loss. The management of CLBP is fundamentally enhanced by addressing these factors, rather than focusing purely on structural repair.

Prominent Yellow Flags include:

-

- Fear Avoidance and Kinesiophobia: This is the strong belief that pain indicates damage and that movement itself is harmful. This belief leads to reduced activity, which causes muscle deconditioning and stiffness.

-

- Catastrophizing: Excessive worry, rumination, and magnification of the pain experience.

-

- Emotional Problems: Co-morbid anxiety, depression, and significant life stress.

If a person avoids movement due to fear, they fall into a difficult cycle: reduced movement leads to temporary pain relief, but also leads to deconditioning. This weakness reinforces the belief that movement is dangerous (kinesiophobia), leading to further psychological distress, which ultimately makes the pain experience more severe. Effective management, therefore, must focus on education to dismantle these maladaptive beliefs and promote active participation in life and work.

Occupational characteristics also influence risk. High physical demands (frequent bending, twisting, lifting) are obvious risks. However, even in less physical jobs, poor psychosocial characteristics—such as high time pressures, low job control, or poor social support at work—significantly increase the risk of low back pain.

Who Does It Happen To?

While anyone can experience back pain, certain demographics and occupational groups face elevated risk for developing persistent, chronic symptoms.

Demographics and Age

Chronic back problems affect people of all ages, though prevalence tends to rise with age, peaking between the ages of 65 and 74 (27% prevalence). However, it is important to note that the majority of sufferers—an estimated 77%—are within the working age bracket (15–64 years). This high proportion of working-age individuals highlights the significant economic and social impact of CLBP on productivity and quality of life in the community. Prevalence is similar between males and females.

Occupational Risk Profiles

Risk profiles are diverse and often reflect the interaction between physical and mental demands:

-

- Sedentary Workers: Individuals who spend long hours in static positions, such as office desk workers, may not face high physical intensity, but they are vulnerable to the strain of prolonged posture and the influence of psychosocial stress (low job control, time pressures) that contribute to CLBP.

-

- Manual Labourers: Those whose jobs require repeated heavy lifting, bending, or twisting are prone to biomechanical stress that leads to degenerative changes in the spine.

-

- Other Factors: People with low levels of physical activity, poor overall health, or other chronic conditions are also at a higher risk. Since CLBP often coexists with other health issues—72% of sufferers live with one or more other chronic conditions, including mental and behavioural conditions (43%)—comprehensive care must address the patient’s overall health profile.

Symptoms and Impact

The symptoms of chronic low back pain are defined by their persistence and are distinct from the sharp, immediate pain of an acute injury.

Hallmark Symptoms

The features of CLBP are varied, but typically include:

-

- Persistent Aching: A deep, dull, or generalized ache in the lumbar region, often present for months or years.

-

- Stiffness: The back often feels tight or stiff, especially after periods of inactivity. Stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes in the morning may warrant further investigation for inflammatory causes.

-

- Positional Sensitivity: Pain that is notably worsened by specific postures (such as prolonged sitting or standing) or movements (bending forward or extending backward).

-

- Fluctuating Intensity: The pain intensity can vary from a low, manageable ache (e.g., 4/10 at rest) to a sharper pain with movement (e.g., 7/10 with activity).

-

- Referred Pain: Pain may radiate into the buttocks, groin, or upper posterior thigh. This is generally considered distinct from true radicular pain (sciatica) that follows a clear nerve pathway down the entire leg.

Impact on Functional Ability and Quality of Life

CLBP is the third leading cause of disease burden in Australia because it severely limits a person’s ability to function and participate in life. The consequences extend far beyond physical discomfort:

-

- Functional Limitations: Patients experience difficulty performing daily activities, reduced capacity to sustain work hours, and withdrawal from social or family activities.

-

- Psychological Distress: The constant nature of the pain leads to elevated rates of psychological distress. Individuals with chronic back problems are significantly more likely to report poor perceived health and very high levels of psychological distress, anxiety, and depression compared to the general population.

-

- The Avoidance Cycle: The psychological burden is often linked to the fear avoidance behaviours discussed previously. When pain is associated with high emotional distress, the patient is more likely to develop kinesiophobia, leading to further physical limitations. This complex interaction demonstrates why addressing mental well-being is integral to successful physical recovery.

How to Help / First-Line Interventions

Clinical guidelines consistently emphasise that the first line of intervention for low back pain—both acute and chronic—should be non-pharmacological and centred on active self-management and patient education.

Prioritising Active Management

The primary goal of self-management is to break the cycle of fear avoidance and restore confidence in movement.

-

- Stay Active and Engaged: Continued functional participation in work and daily activities is crucial for long-term success. Patients should be encouraged to maintain movement within comfortable limits, counteracting the belief that pain means damage.

-

- Movement and Strengthening: Structured, regular movement and exercise are vital. This includes building general strength and endurance, as well as specific trunk muscle activation. A simple and effective exercise, like the Pelvic Bridge, helps strengthen the core and gluteal muscles, providing essential support and stability to the lower spine.

-

- Postural and Ergonomic Awareness: Simple modifications to everyday habits can dramatically reduce mechanical strain. This includes adjusting seating positions, ensuring ergonomic desk setups, and practicing safe lifting mechanics.

-

- Simple Modalities: Applying superficial heat has been shown in evidence to be a helpful non-pharmacologic treatment option for low back pain. Ice may also provide temporary comfort for acute flare-ups of chronic pain.

Other Treatments or Proven Interventions

Effective chronic pain management often involves a multidisciplinary approach. It is important for patients to be aware of the full spectrum of evidence-based conservative options available, delivered by various healthcare professionals.

-

- Physiotherapy and Exercise Physiology: These fields focus intensely on prescribing progressive exercise, improving mobility, and enhancing functional training. Exercise physiologists specifically utilise strengthening, endurance, aerobic, and aquatic exercise interventions tailored for chronic LBP.

-

- Manual Therapies: Acupuncture and massage are often utilised to manage pain and muscle tension. Guidelines acknowledge these as useful non-pharmacological options, particularly when combined with exercise and education.

-

- Pharmacologic Interventions: If non-pharmacologic options are insufficient, or if the pain is acute and severe, pharmacologic treatments such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or skeletal muscle relaxants may be selected by a clinician.

Successful long-term management requires collaboration, ensuring that the patient receives the care best suited to their individual needs, without bias toward any single profession.

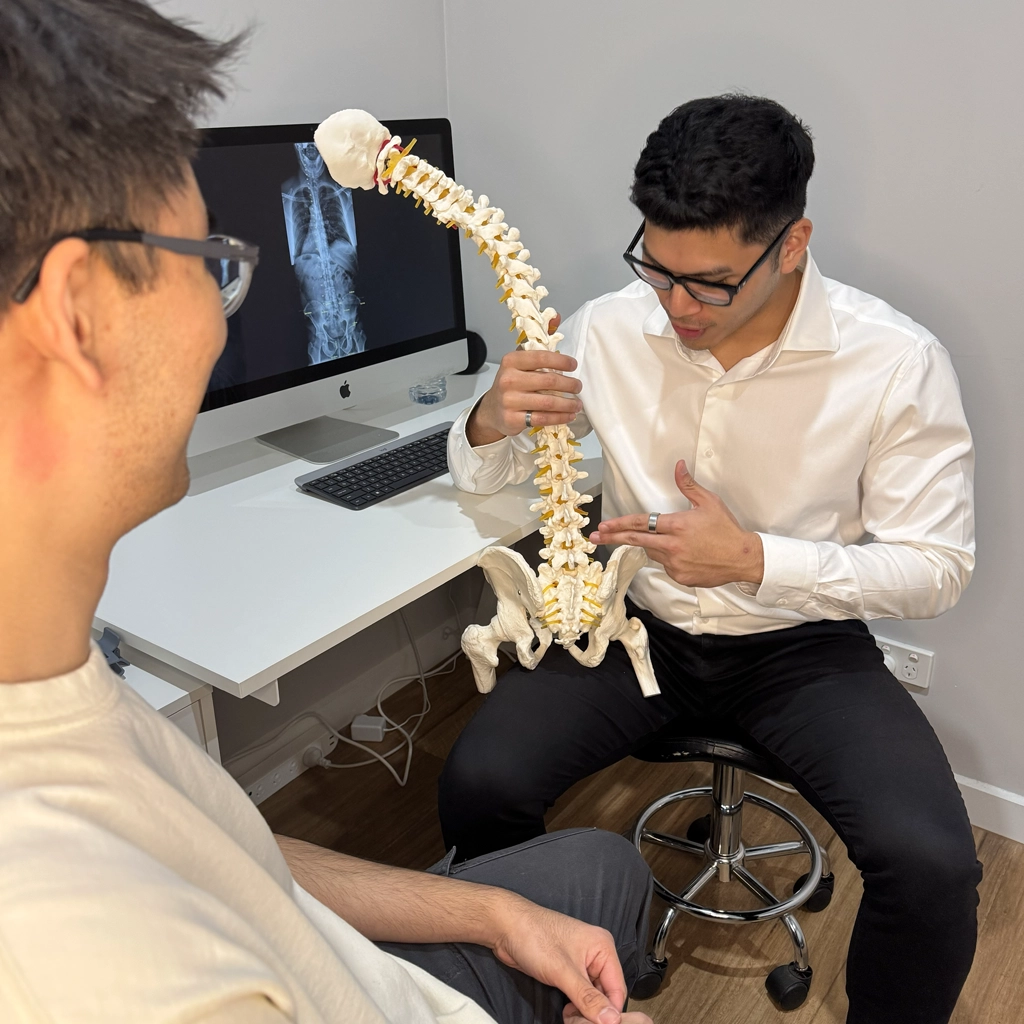

How Chiropractic Helps Manage Chronic Low Back Pain

Chiropractic care offers a targeted, conservative approach to managing CLBP, integrating manual therapy with rehabilitation and patient education to improve physical function and reduce pain reliance.

Comprehensive Assessment

Chiropractic management begins with a detailed assessment aimed at individualising the treatment plan:

-

- Detailed Case History: The chiropractor gathers a thorough history of the pain, including onset, duration, location, and the specific factors that aggravate or alleviate symptoms. Critically, this process includes screening for psychosocial risk factors (Yellow Flags) to understand the patient’s beliefs about their pain and their movement behaviours.

-

- Physical Examination: This assessment involves evaluating spinal mobility, muscle strength, joint function, posture, and stability to identify functional limitations and mechanical irritations contributing to the persistent pain.

-

- Imaging: Imaging such as X-rays or MRI scans are not routinely used for chronic low back pain unless specific “red flags” (signs of potentially serious pathology like fracture, tumour, or infection) are present, or if the history warrants deeper diagnostic clarity.

Multimodal Treatment Strategies

Chiropractic care for CLBP is most effective when delivered as a multimodal approach, targeting various aspects of the condition simultaneously. At Ringwood Chiropractic, treatment combines manual techniques with active rehabilitation to ensure sustained results.

-

- Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization (SMT): Spinal manipulative therapy involves highly specific, controlled movements applied to the spinal joints. Evidence suggests that SMT may assist in managing pain and improving functional movement in patients with CLBP, producing effects comparable to other recommended conservative therapies.

-

- Soft-Tissue Therapy: Addressing the surrounding muscles and connective tissues is essential. Chiropractors often incorporate soft-tissue techniques, including massage and myofascial release, to alleviate muscle guarding, reduce tension, and complement the joint work. Ringwood Chiropractic offers in-house massage and myotherapy, allowing for integrated treatment plans.

-

- Rehabilitation Exercise Prescription: This component is critical for long-term success. Specific exercises are prescribed to improve trunk muscle endurance, enhance stability, and restore movement control. By building strength and confidence, the patient can actively challenge the fear avoidance behaviours (kinesiophobia) that perpetuate chronic disability.

Biomechanical Mechanisms of Benefit

Chiropractic interventions aim to improve function primarily through biomechanical and neurological modulation:

-

- Restoring Joint Function: Manipulation and mobilisation can assist in restoring proper joint movement and alignment, which may help reduce abnormal mechanical stress on structures like discs and facet joints.

-

- Neurological Modulation: Manual therapy provides powerful sensory input to the central nervous system, which can help modulate pain signals and temporarily reduce pain perception. This helps break the pain-spasm-pain cycle often seen in chronic conditions.

-

- Promoting Active Movement: By improving initial mobility and reducing pain sensitivity, chiropractic care helps patients transition successfully into the active rehabilitation phase, which is necessary for reversing the physical deconditioning associated with chronic pain.

It is important for patients to know that chiropractic care is generally considered safe for managing chronic low back pain. While some people report minor, temporary side effects like local soreness or stiffness after an adjustment, serious adverse events are exceedingly rare. Clinicians responsibly inform patients of potential risks associated with SMT.

Your Next Steps

Chronic low back pain demands a dedicated, individualized management strategy. Understanding the complex interactions between physical and non-physical factors is the first step toward reclaiming movement and quality of life.

If persistent back discomfort is limiting your ability to work, enjoy hobbies, or simply move without restriction, a professional assessment is essential to determine the precise nature of your condition and rule out any specific underlying pathologies.

If you’re in Ringwood or nearby suburbs, our experienced chiropractors can help you find relief and restore movement. Book a comprehensive initial consultation today to start your journey toward better functional health.

Other Options: A Collaborative Approach

Optimal management of CLBP often requires a team effort. Ringwood Chiropractic maintains a collaborative attitude within the healthcare community, recognising that multidisciplinary care leads to better outcomes for complex chronic conditions.

Depending on your specific needs, the team may recommend collaboration with or referral to other healthcare professionals, including General Practitioners (GPs), Physiotherapists, or Exercise Physiologists. Furthermore, the clinic provides integrated services through qualified staff, including Naturopaths, Myotherapists, and Massage Therapists, ensuring a holistic approach to address all contributing factors to your chronic pain.

References

Shifrin, V. Y., et al. (2024). Chronic Low Back Pain Management. Seminars in Spine Surgery, 36(1), 101112. (Cited for history taking and individualized treatment) 10.. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2016). Impacts of chronic back problems. Retrieved from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/impacts-of-chronic-back-problems/summary

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2023). Back problems. Retrieved from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/back-problems

Chou, R., Qaseem, A., Snow, V., Casey, D., Cross, L. W., Shekelle, P.,… & Shaukat, A. (2007). Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(7), 478–491. (Cited in relation to evidence grading and non-pharmacologic recommendation)

Coronado, V. G., & Shifrin, V. Y. (2024). Low Back Pain, Chronic. StatPearls. (Cited in relation to CLBP definitions and impact)

Coulter, I. D., Crawford, C., Vernon, H., Hurwitz, E. L., Khorsan, R., Booth, M. S., & Herman, P. M. (2018). Manipulation and mobilization for treating chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Spine Journal, 18(5), 896–905. (Cited in relation to SMT efficacy and safety)

Dagenais, S., Tricco, A. C., & Bachmann, S. (2010). Chiropractic care for low back pain: a systematic review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Cited in relation to multimodal intervention effects)

Huang, M., Chen, J., Feng, Y., et al. (2022). Association of spinal manipulative therapy with the efficacy of clinical practice guidelines for musculoskeletal conditions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 103(9), e25. (Cited in relation to CPG recommendations for SMT)

Ko, M. S., et al. (2024). Degenerative Chronic Low Back Pain: Evolving Clinical Definitions, Pain Classifications, and Comprehensive Pain Evaluation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 812. (Cited for anatomy, modern definitions, and pain mechanisms)

Page, B., & Laing, C. (2021). Exercise for Chronic Low Back Pain: Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 51(11), CPG1–CPG74. (Cited for specific exercise recommendations)